Year 11 Glen Waverley student Kirwan has won the 2023 Premier’s 'Spirit of ANZAC' prize, an annual competition open to Victorian school students in Years 9 to 12.

The prize invites students to write a piece that explores the ANZAC legacy post-World War I and its ongoing relevance to multicultural Australia.

Excitingly, with the 11 other students from across Victoria who were also awarded the prize, Kirwan will embark on a trip to Türkiye next month to retrace the steps of the ANZACS.

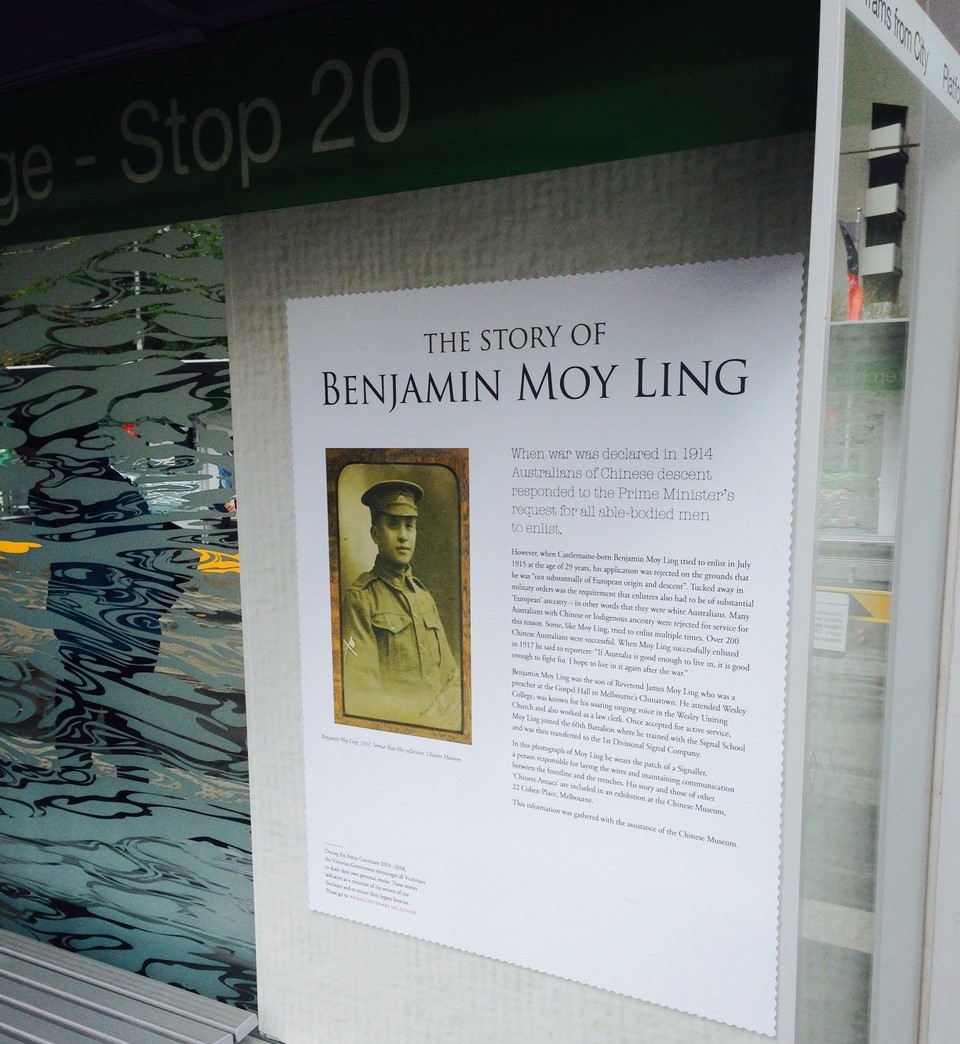

In her piece, she draws poignant links between her mother’s immigrant story and that of Benjamin Moy Ling (OW1900) who served in the Australian forces in World War I.

Tales of Poppyseed and Poppies

Orange and poppyseed cake may seem like an inconspicuous baked good, but whenever it is brought up in conversation, my mother never fails to mention it was served at her citizenship ceremony, some 24 years ago. My mother emigrated from Hong Kong when she was in Year 10, as young as I am now. In her time as an Australian citizen, she has displayed resourcefulness, fidelity and endurance by overcoming the difficulties of creating a true home in a foreign land and raising my brothers and I.

Many other stories mirror the themes that overarch my mother’s journey. Benjamin Moy Ling (OW1900) served in the 4th Divisional Signalling Company in 1918 and was born in Australia to immigrant parents. Because his father was from Canton (or Guangzhou), Ling likely grew up speaking Cantonese, a language I was raised in by my grandparents and mother. I, too, am a second-generation immigrant, but I can only speculate as to whether he also struggled with maintaining strong ties with his language and culture, and identifying who he was in the context of his heritage and diverse upbringing.

Ling was originally rejected due to being ‘not substantially of European origin’. Several other men of Asian descent were also stopped from offering their service to the very country they lived in, like Hunter Poon, William Wong and Samuel Tong-Way; however, in a display of the ANZAC spirit, they went on to reapply, often several times, showing endurance and reckless valour for repeatedly signing up for a fatal war. Ling truly believed in the cause, and reportedly said, ‘If Australia is good enough to live in, it is good enough to fight for.’ After the war, Ling contributed to the community by being active in the Methodist Church and founding the Young Chinese League, which encouraged social connections in immigrant families and promoted better understanding of Chinese heritage.

Benjamin Moy Ling and my mother are both Australians that exemplify the ANZAC spirit, regardless of their ancestry. In fact, all the ANZACs at Gallipoli, except the 70 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander soldiers, had ancestors from different lands, a quality they share with Ling and my mum. The ANZAC spirit has not changed since the first time it was quantified, and indeed since well before then. While the context of the spirit has transformed - my mother and Ling had different trials and tribulations - at the very core, both showed enterprise, resourcefulness, endurance and many other tenets.

Whether it was the harshness of rejection for Benjamin after enlisting, or the celebration of orange and poppyseed cake for my mother, both have had defining highs and lows on this land, and both reacted to these moments with the true spirit of an ANZAC. The ANZAC story and legacy remains as a reminder of how all Australians continue to maintain the ANZAC spirit, even as the nation evolves.

Written by Kirwan (Year 11)