Our June issue of Lion featured Year 11 Glen Waverley student Kirwan’s poignant Tales of Poppyseed and Poppies, a personal reflection on the ANZAC legacy that won her the 2023 Premier’s Spirit of ANZAC prize. Together with the 11 other winning Victorian students, she travelled to Türkiye in early July for an eight-day study tour of Istanbul and the Gallipoli peninsula. Here, she reflects on that journey.

'Türkiye’s oceans and rivers around Istanbul and the Gallipoli peninsula are a sparkling blue, even clearer than some of the most beautiful beaches in Australia. At the Ari Burnu cemetery, the graves of Commonwealth soldiers overlook this calm, pristine water in a peaceful, bittersweet kind of way. This final resting place of both the bodies and memories of fallen soldiers is somewhat of a contradiction to the way in which they died, but it reflects how Turkish people turned around and forgave the very ANZAC soldiers that invaded their homeland in a violent manner. The gardens are well tended to by locals, and there is no rubbish in sight.

To have the opportunity to visit a country with incredible historical significance was really touching. In Australia, much of our Indigenous heritage was destroyed, along with their stories, languages and songs, and whatever physical remnants that have been left behind are often placed behind a glass barrier to prevent any damage.

This happens a lot less in Türkiye. In Istanbul, our tour guide pointed out a gorgeous fountain gifted by Kaiser Wilhelm II to the Ottoman Empire; we saw a stray dog washing its feet in said fountain, while others washed clothes and hands. Even sacred sites, like the Hagia Sofia, had walls covered in initials, where you couldn’t tell if they had been left by tourists or ancient Romans. I touched the walls of the city of Troy and stood upon roads that had been paved nearly 3000 years ago, and everyone around me acted like this was ordinary.

This casualness that people had with their surroundings challenged a lot of pre-conceived perspectives I subconsciously held about the world around me. It’s easy to consider the present to be detached from the past when you are living in Melbourne, like two works from the same author: similar in style and form, but different in context and characters. It took this experience in a foreign country to make me realise that they are inextricably linked. The present cannot be without the past, and the past is never really gone, it just permeates in different forms, whether that be language, customs, traditions or monuments.

I learnt a lot about the spirit of the ANZACs while I was there, which was the intention of the trip, funded by the Victorian government. It also reminded me that there are two sides of every story. It’s easy to forget that the Turkish people also sent away their sons, fathers, brothers and husbands with tears in their eyes when they were invaded. But somehow, with grace and humility, the Turkish people opened their arms to the mourning mothers of the ANZACs, for ‘having lost their lives on this land, they have become our sons as well', as Mustafa Ataturk put it. The Turkish won the battle of Gallipoli, but saw no need to inflict further harm after the war was over.

This kindness extends to today. People got excited when they learnt I was Australian (not American) and would rush to tell me about their relative that was studying here, or the summer trip they had taken to Brisbane. It’s a clear example of how the past still has a place in the present, and how modern friendships are both a reflection and a product of human connection in history. The lack of animosity between previous enemies should be celebrated, alongside the courage of the ANZACs. Recognising that both sides were equally tenacious and resilient in horrible circumstances is at the core of understanding the ANZAC spirit and passing this spirit on.

My passion is in remembering and sharing stories, and so I share this with you.

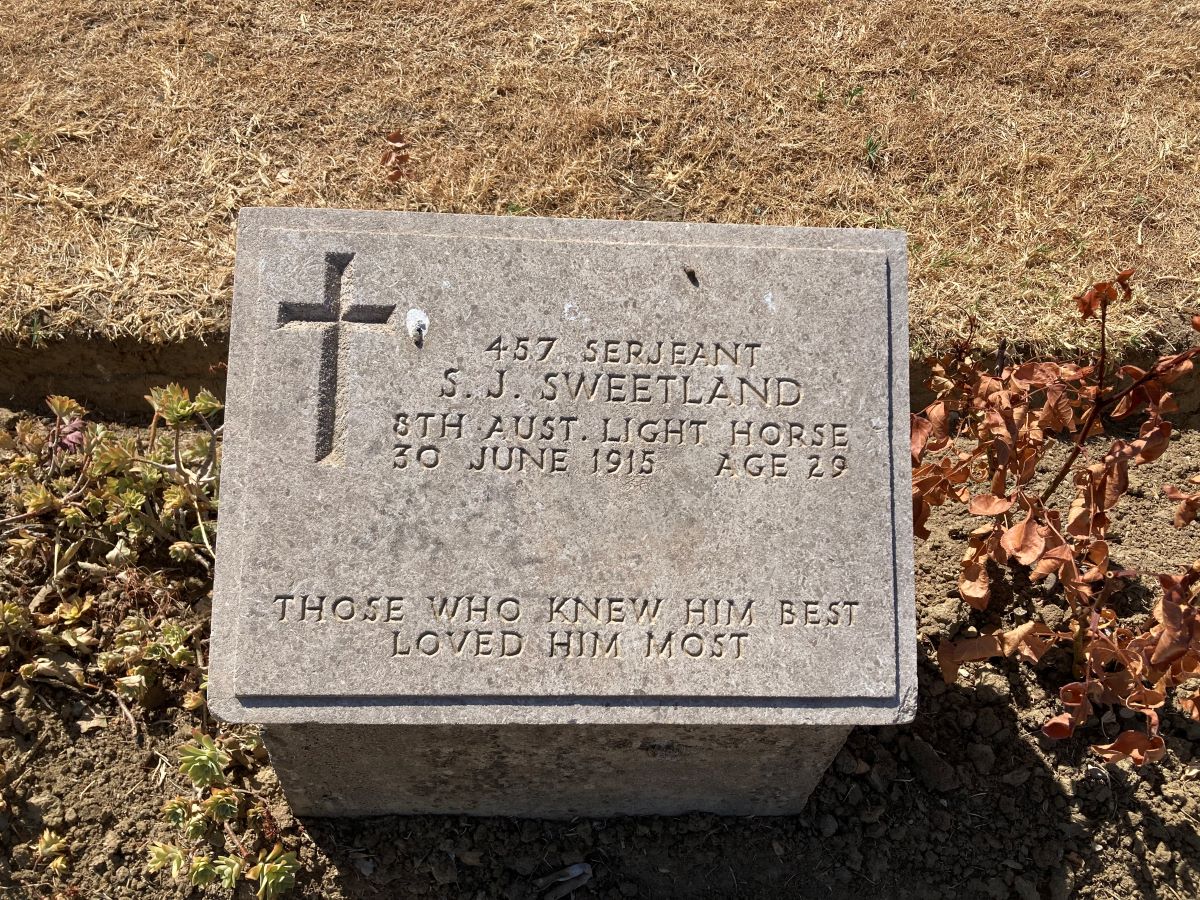

At the Ari Burnu cemetery, with the ocean in the background and the sun beating down relentlessly, I visited the grave of Sergeant Stephen James Sweetland, a clerk who lived in Box Hill, only three minutes away by train from my local station. Like me, he went to Wesley. His first year was in 1895, probably 3rd or 4th grade, and he was a talented athlete. He was clearly a strong and daring individual with a clear sense of justice, as he enlisted less than two months after the war broke out and was put into the 8th Light Horse Regiment. He died, aged 29, not too far from the sea that is now his view while he rests for eternity. His grave has this inscription: ‘Those who knew him best, loved him most.’