<< Back to Lion August 2020

Archives

A pound of prevention is worth a ton of cure

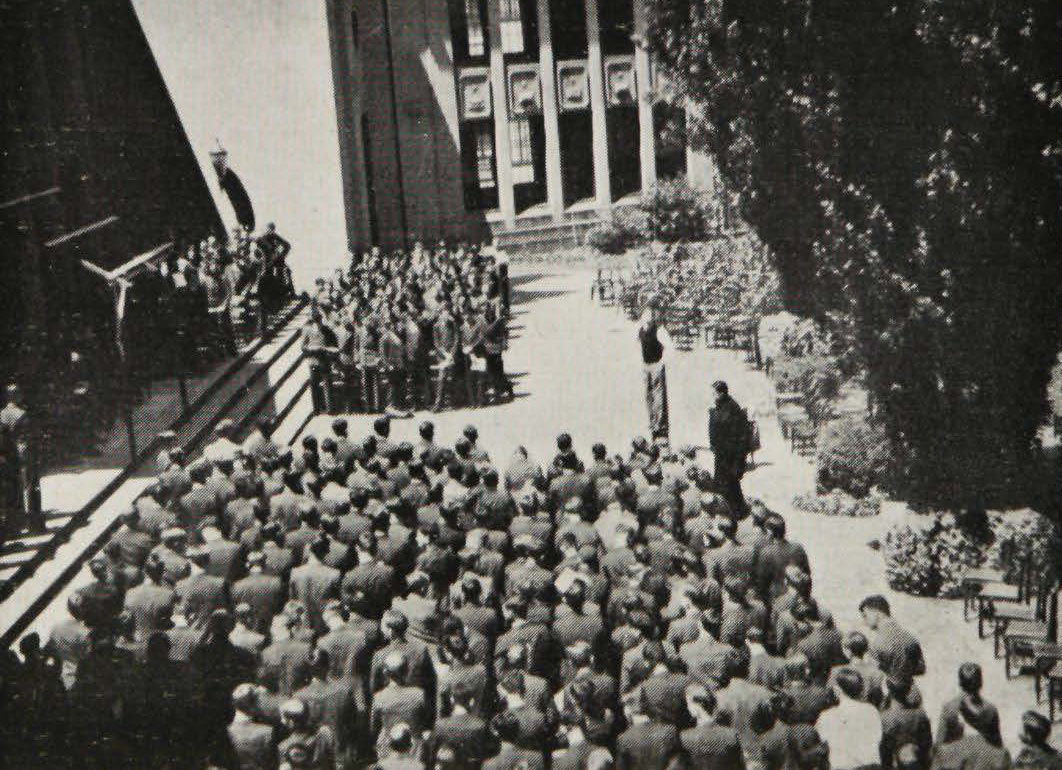

Image above: Speech Day in 1946 was held outside as were school assemblies at Wesley, as one of many health measures to contain the spread of the viral spread of poliomyelitis.

As we face the challenge of COVID-19 and perhaps the challenge of pandemics to come, it’s worth remembering that we at Wesley College and in the wider community have been here before, as Kenneth Park explains.

‘A pound of prevention is worth a ton of cure’: these salutary words were published in the 1949 edition of the Wesley College Chronicle, when the nation was dealing with the reality of the polio epidemic. Today, we face the challenge of SARS-CoV-2 and the disease it causes, COVID 19. Armed with the experience of past pandemics, we and all Australians are responding to the pandemic threat with lockdowns, social distancing, travel restrictions and schooling at home, confirming that prevention remains our best course of action in the absence of a cure.

Public health measures to ‘flatten the curve’ in Australia earlier this year slowed the spread of SARS-CoV-2 and bought time so our health system could prepare for COVID-19. We’ve seen current parents, past parents and graduates working at the front line of our health services sector to manage public health, build acute care capacity in our hospitals, test for SARS-CoV-2, care for patients with COVID-19 and undertake vital medical research.

Wesley and the challenge of COVID-19 in 2020

Work by Dr Alan Finkel, Australia’s Chief Scientist and a past Wesley parent, in leading a Commonwealth taskforce to manufacture ventilators domestically while Australia flattened the curve in April ensured hospitals had the acute care capacity to treat critically ill COVID-19 patients, adding some 5,000 ventilators to the existing 2,200 in Australia’s ICUs.

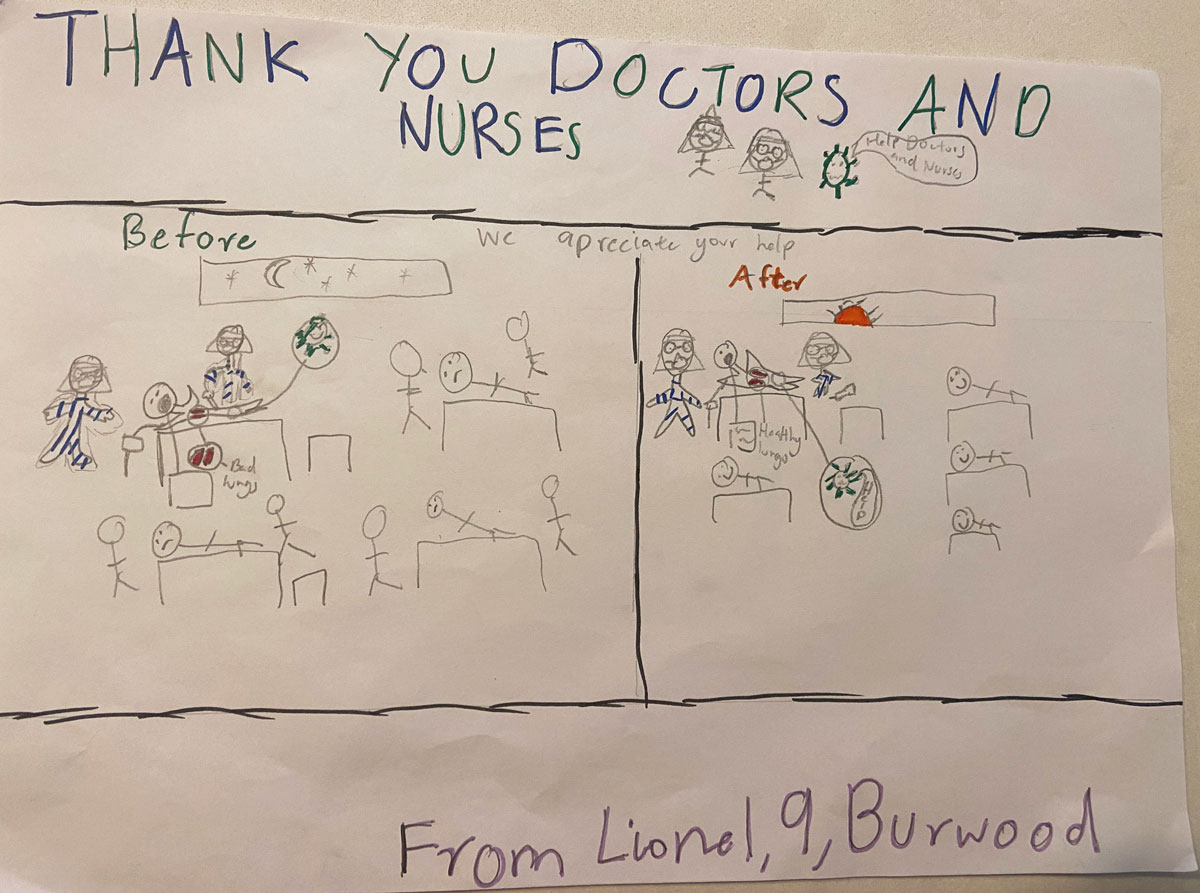

A small group of health professionals from the Chinese community in Melbourne founded MedFamily to support frontline health professionals. Guided by a management committee of seven members that includes four parents from Wesley’s Glen Waverley Campus led by Lin Lin, a Victorian Department of Health and Human Services staffer, MedFamily mobilised in April to deliver personal protective equipment valued at more than $150,000 to six hospitals across Melbourne. Every carton of donated equipment was delivered with a drawing and message of thanks from the children of MedFamily’s 300-plus volunteers, the brainchild of Lin’s son Lionel Chan, a Year 4 student at Glen Waverley.

The global effort to develop accurate tests for SARS-CoV-2, and trial vaccines, received a major boost back in January when Dr Julian Druce (OW1982), Head of the Virus Identification Laboratory at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, successfully grew SARS-CoV-2 from a patient sample – and shared this with labs around the world.

Meanwhile, students, their parents and staff all did their part to flatten the curve, mobilising to enable learning from home through Wesley’s blend of timetabled live virtual classrooms and self-paced classes.

Our Wesley history reveals we have been in like circumstances before, and we have responded in like fashion, working together to help each other and contribute to a better future. Our history also provides an insight into the impact of epidemics past. Past editions of the Chronicle, first published in 1877, reveal that influenza, more commonly called ‘the flu,’ was a constant threat. There are numerous references to boys coming down with influenza. Indeed, a schoolboy sporting star coming down with influenza was frequently used to explain a woeful team performance on the field.

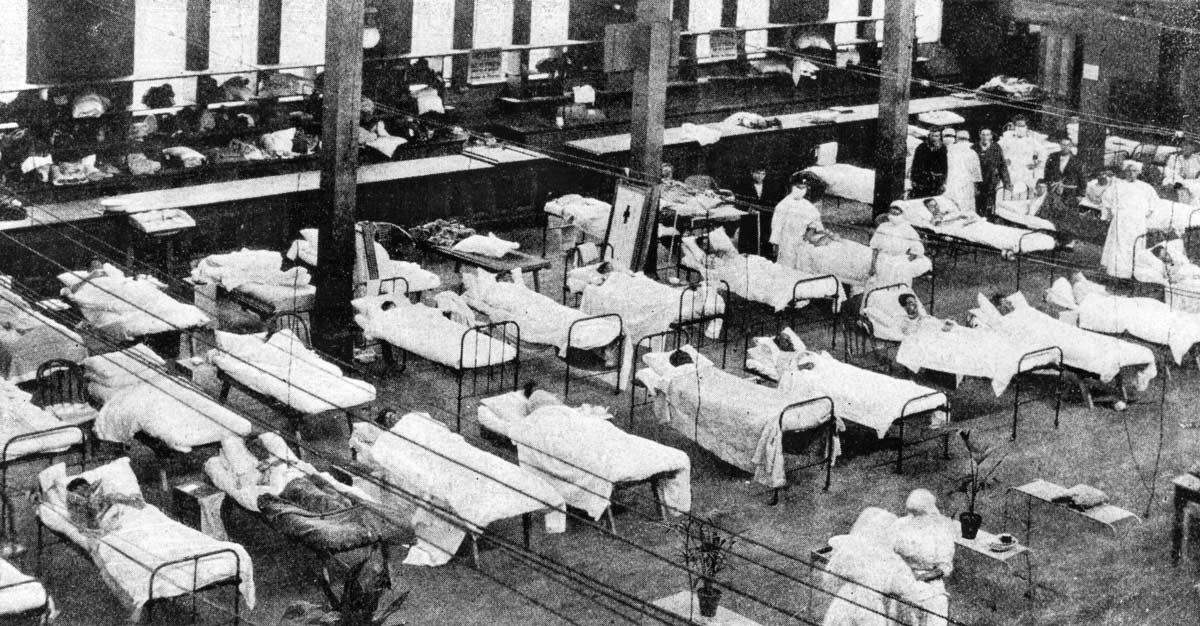

The H1N1 influenza – or Spanish Flu – pandemic towards the end of the First World War had a devastating global impact. Spain, a neutral nation at the time, was one of the few countries in 1918 to report the spreading illness. This and the infection of King Alfonso XIII created the false impression that Spain was especially affected, which gave rise to the name, ‘Spanish Flu.’ The 1918-19 pandemic infected an estimated 500 million people – about a third of the world’s population at the time – and the estimated death toll was somewhere between 17 and 50 million, but possibly as high as 100 million.

One of the deadliest pandemics in human history, Spanish Flu rivalled the Black Death of the 14th century, although it only reached Australia later in 1919 and led to a relatively small number of deaths, estimated at about 12,000.

The similarities between strategies to manage the spread SARS-CoV-2 and Spanish Flu are striking. According to researchers Peter Curson and Kevin McCracken, Australia fared better than other nations because its maritime quarantine policy delayed the arrival of the virus until 1919, schools were closed and limits put on public gatherings, and preventive cough etiquette, hand washing and disinfection were encouraged. When it comes to impact, however, it’s the differences that are striking: state and Commonwealth governments in our relatively young federation failed to cooperate and an estimated two million Australians were probably infected although researchers had yet to identify an effective test and were ill equipped to treat secondary bacterial infections since antibiotics like penicillin only came into general use in 1945.

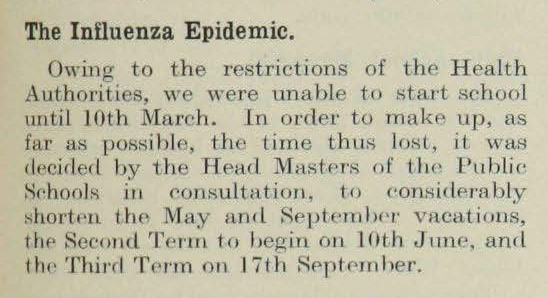

The reach of Spanish Flu extended to Wesley College. According to the 1919 Chronicle, the school year was delayed and other preventive steps were taken, including the postponing or cancelling of many sporting fixtures. One item by Headmaster LA Adamson records with some very personal and sad words the impact on OWs who had just survived the terror of war only to succumb to influenza. ‘JH Coles (1905) (Gunner, 23rd Battery 2nd F.A. Brigade), died of influenza on 28 November, a little more than a fortnight after the Armistice. He had been with us for ten years, as dayboy or boarder, having entered as a small boy of eight in the Prep. He became a Prefect and was the centre forward of the champion 1914 football team, coached by Mr (later Major) Harry Kaighin during Mr Stewart's absence in England. When he enlisted, on leaving school, Jack Coles was gloomy about his health, but that had all passed off, and he was cheerful and fit – safe, apparently, from danger, when the fatal influenza, which cost us all our post-armistice deaths, seized him.’

Preventive public health measures to address what later came to be known as Spanish Flu, including delaying the beginning of the school year and the postponing or cancelling of many sporting fixtures were reported in the Chronicle in 1919.

The threat of influenza would only be reduced more recently with the development of more effective treatments. While the impact of the new strain of Spanish Flu that caused the 2009 ‘Swine Flu’ pandemic was substantial, with between 150,000 and 575,000 deaths worldwide in 2009, a vaccine was available. Today, many of us are regularly vaccinated against the current strains of flu.

Wesley and polio in the 1940s

In the late 1940s, the College faced another viral threat: poliomyelitis. From the beginning of the 20th century polio epidemics had begun to appear in Europe and soon after in the United States of America. By 1910, polio epidemics became regular events throughout the developed world, primarily in cities during the summer months. During the 1940s and ’50s, polio would paralyse or kill more than half a million people worldwide every year.

Again, the similarities between strategies to manage the spread of SARS-CoV-2 and poliomyelitis are striking.

The primary measure was to put limits on public gatherings and practise social distancing. School assemblies at Wesley were held outdoors; no guest speakers were invited for any event; and many interschool activities were cancelled. At the time Wesley had a huge number of student societies ranging from book binding to lifesaving. All had to suspend or dramatically curtail their operations. The school day was shortened to enable students to use off-peak public transport to and from the school. The changes are nicely summed up in the Chronicle of 1949.

‘The main sporting fixtures – our own House Sports and the Combined Sports – were held as usual. It was decided to hold Standard Tests for those who wanted to attempt them, but so as to reduce over-fatigue as much as possible, they were not to count in the Cock House Competition. Chapel Services have been held in the Adamson Hall before “segregated” audiences to try to limit contacts.

‘The bulk milk and ice cream supplies to the tuckshop have been discontinued. Now all ice cream sales are in the form of wafers and dixies. Also, the School swimming pool has been closed.’ As a result, ‘It has been therefore a somewhat empty term, and particularly difficult for the boarders. But if these precautions had any effect in shielding us from the present epidemic, they have been fully justified.’

Preventive public health measures were again put in place to address poliomyelitis during the 1940s and ’50s, on the principle that, ‘A pound of prevention is worth a ton of cure,’ as reported in the Chronicle in 1949

Nevertheless, the pages of editions of the Chronicle during this period contain many black-rimmed notices announcing the deaths of young current and former students.

Once the polio epidemic had passed the Chronicle lauded the resumption of normal school routines. ‘With the passing of the “polio” epidemic, we have returned, with great satisfaction, to the Chapel, for it is a continual source of pride and joy to us. Its soaring walls, its rich panelling, soft light, mellow organ, all create an atmosphere in which “the beauty of holiness” becomes something more than a mere phrase. We have found it well within our reach to approach our worship there in a spirit of quiet expectancy.’

While the availability of polio vaccines has removed the threat of this insidious disease today, a Debating Society report in one edition of the Chronicle makes for interesting reading. ‘On the last Club period of last term we were hosts to the Melbourne Girls' Grammar Discussion Club, with whom we discussed such topics as whether the United Nations is a failure, and whether we have any right to kill monkeys to make the Salk polio vaccine.’ Politics and ethical debates were just as important then as they are today.

As we face the challenge of COVID-19 and perhaps the challenge of pandemics to come, it’s worth remembering that we at Wesley College and in the wider community have been here before, and worth remembering that in daring to be wise we must reflect on our past so that we may act in the present for a better future. In the words of Horace, ‘sapere aude, incipe.’ or ‘dare to be wise, begin,’ for our credos makes clear that the enlightened way is forward, and it is for us to take the first step.

Sapere Aude.

Kenneth Park is Curator of Collections, College Archives.

Acronyms explained

Unlike the names for cyclones, which follow an alphabetical list of familiar and alternating female and male first names, there’s no simple naming convention for viruses or the diseases they can cause. So what do H1N1, SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 actually mean?

H1N1

There are three major types of influenza that infect humans called influenza A and B, and a much milder C. A and B viruses have two types of spikes across their surface, called haemagglutinin – H – and neuraminidase – N. A viruses can have 17 different types of haemagglutinin – H1 to H17 – and nine types of neuraminidase – N1 to N9. The 1918-19 Spanish Flu and 2009 Swine Flu were both H1N1 strains.

SARS-CoV-2

SARS-CoV-2 is named for the type of diseases it causes – severe acute respiratory syndrome or SARS – and the specific genus of coronaviruses or CoVs that cause this syndrome. This gives us SARS-CoV, but why SARS-CoV-2? The 2 distinguishes this virus from its predecessor, SARS-CoV, which infected an estimated 8,000 people and killed 774 between 2002 and ’04.

COVID-19

SARS-CoV-2 is the name of the virus and COVID-19 is the name of the disease it causes: ‘co’ refers to corona, ‘vi’ to virus, ‘d’ to disease and ‘19’ to 2019, when the virus was first known to have appeared.