STEM programs at Wesley are providing students with the tools they’ll need to help surmount some of the world’s most pressing challenges, and survive and thrive in our changing world. Paul Munn reports.

STEM. The simplicity of the acronym belies the complexity that lies behind it. Referring to the confluence of science, technology, engineering and mathematics, STEM is an approach to learning that integrates these disciplines to offer possibilities far beyond what each offers by itself. For students, a contemporary STEM education still has elements of the traditional in it, namely, deep discipline knowledge, but it’s combined with this integrated approach, and the glue holding it all together is some very important – and very transferrable – soft skills, such as problem-solving, creativity, critical thinking and collaboration.

Why does STEM matter?

The potential for STEM-skilled people to make important contributions to our global community is significant, as the current global COVID-19 crisis makes eminently clear, but even on the purely pragmatic level of future careers, having STEM skills makes sense. Government labour force data shows that STEM jobs are growing almost twice as fast as other jobs, with the trend set to continue. The digital technology revolution has completely shifted the way we learn and work.

Head of Design and Technology at the St Kilda Road Campus, Gayathri Wijesekera, observes that, ‘Jobs that didn’t exist five years ago are now the strongest drivers of economic growth.’ She sees it as her faculty’s responsibility to nurture in students the skills necessary to flourish in the face of change. ‘As a department, we’re focused on allowing students to see the opportunities digital technology provides. The life cycle of a technology is roughly about two years. We don’t have six months to learn something and then take action. Our students need to feel comfortable with being self-learners, to go out and find information, to be adaptive, to be agile.’

So what does STEM look like at Wesley?

In the Primary Years Program (PYP), 2020 marked the arrival of MakerSpaces across our Junior Schools. The MakerSpace is a room crammed with a vast array of age-appropriate tools and materials where, consistent with PYP learning principles, teachers guide their students using a design-thinking model to find solutions to a presented problem, create prototypes to test their ideas and then refine their thinking to make improvements.

According to Glen Waverley PYP Head of Learning Science, Technology and Social Studies, Blair Odom, ‘MakerSpace is not about using the latest gadgets in stand-alone lessons, unrelated to what is going on in students’ lives and the world around them. It’s engaging with projects that build upon what they are already doing in the classroom to increase collaboration, improve problem-solving skills and enhance creativity.’

The new Technology Centre at Glen Waverley is like a ‘MakerSpace for big kids,’ and indeed the skills the younger students learn in the PYP are further developed as they progress into the deeper waters of project-based learning in the Middle Years Program.

A natural part of STEM DNA, and a very powerful teaching approach, project-based learning has become a significant part of the MYP curriculum via Design and Technology, now a core subject for Years 7, 8 and 9 at Wesley.

Examples of the sort of work Wesley students are doing in this space are many and varied. In Year 7, students can opt to learn computer coding, but everyone gets involved in a variety of team challenges, often run as an interdisciplinary unit with the Science faculty. Projects include designing and constructing balloon-powered vehicles, watercraft, glue-less bridges, and robotic fish, the challenges providing an exciting focus for the students and an opportunity to test their designs to the limit.

Innovation and entrepreneurial skills (another important STEM skill-set) are given a healthy workout at Year 8 level. In an exercise designed to address global issues, students at the Glen Waverley Campus design conceptual apps in response to UN Sustainability Goals, then pitch their ideas to guest judges. ‘The pitch is a chance for students to receive industry-standard critiques of their products and to practise their entrepreneurial skills in a lifelike setting,’ says Daniel Galvin, Head of the Design and Technology faculty.

In the same way, Year 8 students at the St Kilda Road Campus have staged pop-up exhibitions of their own innovative prototypes. ‘We’re empowering students with the opportunity to create a product that can help address an issue they’re concerned about,’ says Wijesekera.

In Year 9, students step up to even more sophisticated design and development challenges. An ‘Escape Room’ unit has students designing and creating a working escape room prototype model, which features electronics, sensors, construction and, of course, more teamwork. A Biomimicry unit challenges students to focus on problems connected with urbanisation and overpopulation. They learn from and mimic the strategies found in nature to solve human design challenges and find sustainable solutions.

In Senior School, the real-world links become even more tangible. In collaboration with the Product Design Engineering Faculty at Swinburne University, Wesley’s Design and Technology faculty runs a program in which students in Years 10 and 11 have worked with Swinburne staff in full-day workshops on modelling and rapid prototyping.

In Year 12, Design and Technology students collaborate closely with a client from business and industry, again within a strongly project-based framework. The projects and partnerships are diverse: from developing a sanitary kit for teenage girls in partnership with the Aminata Maternal Foundation to working with the local council to implement design solutions for public green spaces to offset heat island effect. Real-world applications and intense collaboration are hallmarks of the program.

STEM: making powerful things happen

Australia’s Chief Scientist and past Wesley parent, Dr Alan Finkel, has been a strong advocate for STEM for many years. Dr Finkel, who is leading a Commonwealth taskforce to manufacture ventilators domestically to treat patients with COVID-19, maintains that in the midst of all the collaborative effort, deep content knowledge is still critical – it’s the pairing of this knowledge with STEM interdisciplinary skills that makes powerful things happen.

As Dr Finkel explained in an ABC article published in April, the taskforce is making powerful things happen – he and colleagues have added close to 5,000 ventilators to the 2,200 currently in Australia’s ICUs – through teamwork. ‘All hands were on deck,’ he wrote, ‘with the united goal of ensuring Australian ICU units are best-placed to manage the worst impacts of COVID-19.’

Climate change mitigation

Zebedee Nicholls’ (OW2011) story of teamwork is another case in point. Passionate about Physics at Wesley, Zeb studied a Masters of Physics at Oxford, completing it with a thesis in Climate Physics. Currently in the third year of his PhD in Climate Physics at the University of Melbourne, Zeb is researching climate change mitigation, developing models that project global mean warming and sea level rise from man-made emissions of greenhouse gases and aerosols. As Zeb tells it, ‘When (if!) governments ask, ”How quickly do we need to cut our emissions?” researchers like us are the people who answer.’

Deep knowledge indeed, but then there’s a raft of soft STEM skills to go with it. According to Zeb, ‘My entire PhD is problem-solving on both multi-year and hour-to-hour timescales. And cross-discipline communication is a skill I draw on daily. My project is a collaboration between me, my main supervisor (a Physicist by training but also an experienced negotiator working for the German government) and our in-house software engineer, an expert in a different domain. Beyond that, I also work with a few groups in Europe, which brings its own challenges in cross-cultural, cross-timezone and cross-institution collaboration.

‘These collaborators have backgrounds in mathematics, engineering, economics and geography, so quite a range of cross-discipline work. We're all pulling in the same direction, which means there's always a solution; it's just finding it can be the hard part.’

Helping people see again

Creative problem-solving is clearly a common thread across STEM-related professions. For eye surgeon Amy Cohn (OW1993), ‘Creativity and curiosity are absolutely essential to being a good doctor. When you’re creative you think outside the box – you question things, you want to look for alternative solutions.’

An ophthalmologist who specialises in eye diseases and cataract surgery, and a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Eye Research Australia, Amy felt very supported by Wesley in pursuing her career pathway. ‘As a girl who was passionate about sciences and maths, I was always encouraged to follow those interests, and this led to me doing two maths and two sciences in Year 12. I loved that I was challenged to ask questions and supported as I found my path,’ Amy says.

The real-world rewards that Amy has gained in pursuing her passions in STEM are very tangible. ‘I love that my job can help people see again. They can continue working and look into the faces of the people they love. There’s really no greater high from a professional standpoint for me.’

Finding a coronavirus vaccine

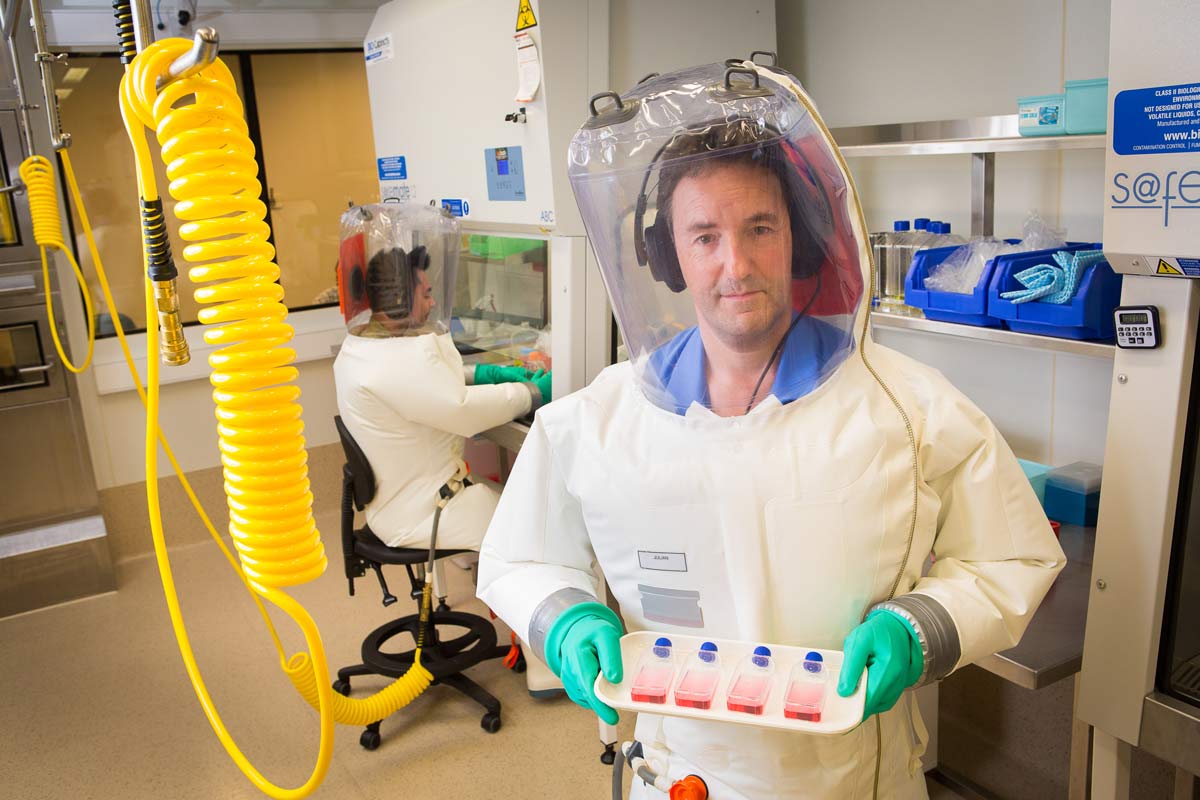

Like Dr Finkel, Dr Julian Druce (OW1982), Head of the Virus Identification Laboratory at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, is working at the STEM coalface and making a real-world difference. Dr Druce made world headlines in late January when he successfully grew the novel coronavirus (now named SARS-CoV-2) from a patient sample – a crucial breakthrough in helping medical scientists accurately diagnose and develop a vaccine and medicines to combat the disease.

After graduating from Wesley, Julian studied at Monash University, completing a Master of Science and PhD in Virology. Among his other professional experiences, he conducted a four-year AusAid-funded teaching and mentor program in Vietnam for improving the diagnosis and detection of avian influenza virus and other respiratory viruses, before joining the Doherty Institute. Jointly operated by the University of Melbourne and the Royal Melbourne Hospital, the Institute is a $210 million facility bringing together hundreds of scientists from different areas – research, diagnostics, teaching, medicine and public health – to collaborate in the fight against infectious diseases: STEM writ large in a professional context.

The first case of SARS-CoV-2 in Australia was diagnosed at 2am on Saturday, 25 January; just two days later, Julian had the virus growing in culture. Speaking later, Dr Mike Catton, Deputy Director of the Doherty Institute, said, ‘How pleased we are to have been able to grow this virus in a very short space of time, directly from a patient sample. That’s an art, and Julian is the artist.’ Needless to say, collaborating with the global community was foremost in their minds. ‘We’ve moved immediately to share this with our international colleagues,’ he said.

From Junior, Middle and Senior Schools, to university and beyond, our students are going out into the world equipped for many opportunities – and the contributions they can make by engaging in their subject passions and using their STEM skills are limitless. As Dr Finkel maintains, it’s developing the deep content knowledge and expertise in a specific discipline and developing the problem-solving, collaboration, creativity and critical-thinking skills that are at the heart of STEM that will provide our students with the agency necessary to thrive in a changing world.

And maybe, like Zeb Nicholls, Amy Cohn and Julian Druce before them, they’ll be there helping address some big questions being asked about our daily lives, or even the future of our planet.

Paul Munn is the Editor of Wesley’s community magazine, Lion, in which this article first appeared.