The Executive Director of The Wesley College Institute for Innovation in Education, Andrew Blair, talks to some early players in the introduction of the International Baccalaureate (IB) at Wesley. Australia was in the midst of significant change in 1993. Our population was just over 17.5 million, Paul Keating was Prime Minister, the World Wide Web was launched, and a more international view was the mantra from Canberra.

In that same year, Wesley took a significant step – the introduction of the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme (IB DP). The College had a Year 12 enrolment of 449 students – two of whom undertook the IB DP. In 1994 that number had grown to 75, within a total cohort of 475 Year 12 students. The State Government had introduced its new and “inclusive” Victorian Certificate of Education (VCE) in 1987, so why at this time of great change in Victorian education did the College choose to introduce a second pathway for our Years 11 and 12 students? This, our twentieth year of teaching the International Baccalaureate Diploma, seemed like a good moment to ask about those motivations, and to understand some of the challenges facing Wesley at the time.

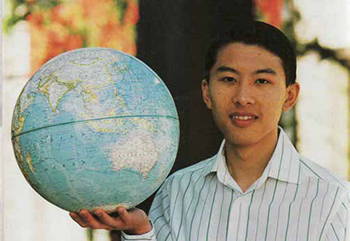

Leit-Chin Siew, a practising psychiatrist in Melbourne, completed the IB DP at the Glen Waverley campus in 1994, returning a score of 45. He was a Wesley student from the Early Childhood Learning Centre through to Year 12, and liked to keep busy at school with a mix of study and music, debating, a bit of drama: things that in my life since school I haven’t been involved in as much, so I enjoyed the opportunity at Wesley to be involved in those things. His parents, who wanted to see Leit-Chin head directly to a medical degree, would have liked him to have been less busy.

He began his Year 11 studies enrolled in the VCE and made the switch to the IB DP because it probably had something to do with the type of assessment. I made a judgement at the time that I was better at exam-based assessment rather than projects… There was an academic broadness to the IB DP syllabus that I found appealing. At the time there was not a conversion table in place to establish a tertiary entrance score for the IB DP; Leit-Chin described his decision to switch as anxiety provoking. I asked him about the risks versus rewards of his decision, and whether in the end was it the right decision for him.

Yes certainly. The broadness of syllabus, the sense of it being a liberal education – [the notion] of learning things because they are important things to learn, not only because of how they will be applied afterwards. For example, I found philosophy to be one the most useful subjects I did at school and not something I have been able to do in that much depth since leaving Wesley.

In what sense, I put it to him, was philosophy useful to him?

We concentrated on political and ethical philosophy, and when I think about how I see those areas now, the grounding I had in philosophy from Wesley influenced it. In my practice as a psychiatrist, ethics is a day-today concern, so from a professional sense it is something that has been important to me.

The IB Diploma included components that were new to Australian education, like the subject Theory of Knowledge, and the concept of international mindedness, so I asked Leit–Chin to describe the impact of these for him.

The Theory of Knowledge (TOK) in retrospect was actually something I took a great deal from. Again it is something I haven’t been able to look at again in great detail. It is quite possible if I didn’t do TOK I wouldn’t have looked into some of those ideas around epistemology. As for international mindedness: I guess there was a sense of not wanting to be over parochial. Thinking about literature in a world sense and studying a second language. My second language was French.

The perspective of the staff in embracing this significant change is a central element of the story. Greg Wilms was teaching at the St Kilda Road campus in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and had not much knowledge and exposure to the IB DP at that time. In 1992 he transferred to Glen Waverley as Head of Business Studies, with the task of coordinating the introduction of Economics into the IB DP at that campus.

This was my first initiation. It was exciting – only a handful of students. It was given a lot of focus but people didn’t know much about it. It was very much learning as you go. There was a lot of preparation for teachers. The nature of the whole IB Diploma was different to the VCE and the philosophy of the VCE. It [seemed to me] to offer a more rounded learning experience.

How did staff source curriculum and find support for the introduction of the new certificate?

It was very much relying on contacting teachers from other schools throughout the world that ran the programme and looking at the International Baccalaureate website and seeing what was required. The documentation was very clear and detailed. I started teaching Business Management in 2001 at a time when only one other school offered the subject. I went to Sydney to observe a few classes at a school offering Business. I also read extensively. It was a matter of going out and finding out things yourself. I needed access to a lot of resources and different teaching ideas.

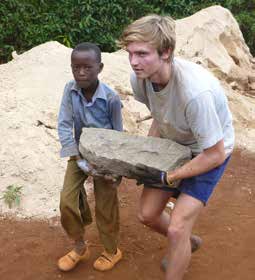

Greg was also involved as the Creativity Action and Service (CAS) program coordinator for Glen Waverley. I asked how central was the CAS philosophy in the introduction? For Greg, it was clearly about students being encouraged to develop initiatives in a broader community, in addition to exploring creative pathways, and learning to function as members of a team.

This approach requires a different strategy for teachers. Would traditional approaches would be less effective in the IB setting? In terms of traditional or non-traditional teaching methods, Greg acknowledges that those taking the IB Diploma seemed instinctively to be self-directed, and to engage in research and inquiry with less direction from the teacher, and to embrace a group experience of learning together and helping each other.

So, logically, I asked Greg how this had impacted on his teaching of the VCE?

Yes I think it has. I am probably someone who is reasonably flexible, but I am more comfortable and more successful when I have the leadership of the classroom agenda. The IB has broadened my ideas within the VCE and [enhanced] my armoury of different approaches to take with students in my classrooms.

Our conversation moved from impacts on the teacher to changing Wesley itself. I asked whether he could identify tangible differences to the College resulting from the IB. He responded by urging how comfortably the IB sits with Wesley’s philosophy for developing the whole person, and providing a diverse range of opportunities and learning experiences, and encouraging individuals to accept responsibility (at least in part) for their schooling. The growth in numbers studying the IB has in turn, he argues, enabled Wesley to grow as well. After all, one of the cornerstones of our educational mantra is diversity.

The present Principal, Helen Drennen, was the senior member of the College staff responsible for the investigation and implementation of the IB in 1993. In the late 80s there was an emergent focus on preparing Wesley for the world of the 21st century. In response to Council discussions, partnerships were forged with schools in our region. Principal David Prest was keen to establish programs that would further provide a more international outlook. Globalisation was the buzz on the world stage, but Wesley’s interest was educational, not commercial. Prest had instructed Ian Ling, then Director of Curriculum, to visit some schools overseas that had programs with an international focus and, as a result of his report, Dr Drennen undertook a staff scholarship project to explore best practice in the International Baccalaureate in other parts of the world. The implementation of the program for Wesley was now only a step or two away.

At this time the VCE, based on the findings of the Blackburn Report, was newly introduced into high schools, and so Wesley needed to consider whether this new certificate could address all of the required components of a Wesley education. The IB door was opening further, as Dr Drennen explains:

The new VCE was developed so that the increasing percentages of the children who stayed at school could undertake it. It was very much a one size fits all and there was openness at the Council level for choice, because one size fits all doesn’t fit with Wesley’s philosophy of making sure there is a pathway for every individual student.

So was the Council focused on best practice, or internationalism, as its prime motivation for considering the introduction of the IB?

I think it was both. I would put the major driver being the internationalism and finding our place in the wider world and preparing students for a world that would engage them directly with the outside world. But at the same time offering a choice – a strong academic program was seen as being very important as well. It was not driven by advantage for tertiary entry, as some people thought, or anything like that, as we didn’t even have a translation table. It had a terrific reputation for academic rigour.

Helen Drennen can now, twenty years on, bring together some perspectives on the difficulties encountered back then. A new Senior College was being opened at Glen Waverley. The VCE was a new model. There was a lot going on. The staff were uncertain, and needed to feel confident that they were well prepared to introduce another new program. But there was enough faith around to believe that this was the way forward.

The parents too, as Helen now acknowledges, shared in this leap of faith, those brave guardians of the initial 124 students in 1992 who that trusted the school enough to allow their offspring to undertake a course for which there was, as yet, no translation table for tertiary entrance, and not even a system in place for releasing results. More than just leaps of faith, one could claim.

Helen Drennen has no doubts now as to the correctness of the decision to broaden Wesley’s offerings:

It has always stuck me as ironic that the outside world saw the IB Diploma as very traditional and old fashioned, whereas it was one of the biggest academic innovations that we could have brought about and it wasn’t outdated. All the myths about it were found to be untrue in practice.